The Apartment

| The Apartment | |

|---|---|

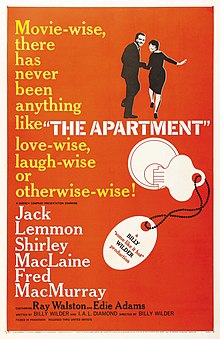

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Billy Wilder |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Billy Wilder |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph LaShelle |

| Edited by | Daniel Mandell |

| Music by | Adolph Deutsch |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates | |

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million |

| Box office | $24.6 million[2] |

The Apartment is a 1960 American romantic comedy-drama film directed and produced by Billy Wilder from a screenplay he co-wrote with I. A. L. Diamond. It stars Jack Lemmon, Shirley MacLaine, Fred MacMurray, Ray Walston, Jack Kruschen, David Lewis, Willard Waterman, David White, Hope Holiday, and Edie Adams.

The film follows an insurance clerk (Lemmon) who, in hopes of climbing the corporate ladder, allows his superiors to use his Upper West Side apartment to conduct their extramarital affairs. He becomes attracted to an elevator operator (MacLaine) in his office building, unaware that she is having an affair with the head of personnel (MacMurray).

The Apartment was distributed by United Artists to widespread critical acclaim and was a commercial success, despite controversy owing to its subject matter. It became the 8th highest-grossing film of 1960. At the 33rd Academy Awards, the film was nominated for ten awards and won five, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay. Lemmon, MacLaine, and Kruschen were nominated for Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Supporting Actor respectively, and Lemmon and MacLaine won Golden Globe Awards for their performances. Promises, Promises, a 1968 Broadway musical by Burt Bacharach, Hal David, and Neil Simon, was based on the film.

The Apartment has come to be regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, appearing in lists by the American Film Institute and Sight and Sound magazine. In 1994, it was one of 25 films selected for inclusion to the Library of Congress National Film Registry.[3][4]

Plot

[edit]C.C. "Bud" Baxter is a lonely office worker at an insurance company in New York City. To climb the corporate ladder, he allows four company managers to take turns borrowing his Upper West Side apartment for their extramarital affairs. Baxter meticulously juggles the "booking" schedule, but the steady stream of women convinces his neighbors that he is a playboy.

Baxter solicits glowing performance reviews from the four managers and submits them to personnel director Jeff Sheldrake, who then promises to promote him provided that Sheldrake also earns use of the apartment for his own affairs starting that night. As compensation for this short notice, he gives Baxter two tickets to see The Music Man. Bud asks Fran Kubelik, an elevator operator in the office building to whom he is attracted, to join him. She agrees, but first has dinner with a "former fling", who turns out to be Sheldrake. When Sheldrake tells her that he plans to divorce his wife to be with her, they head to Baxter's apartment, while Baxter waits outside the theater.

During the company's raucous Christmas Eve party, Sheldrake's secretary, Miss Olsen, tells Fran that her boss has had numerous affairs with other female employees, including herself. Fran confronts Sheldrake at Baxter's apartment; he claims he loves her, but heads back to his family in White Plains.

Realizing that Fran is the woman Sheldrake has been taking to his apartment, Baxter lets himself be picked up by a married woman at a local bar. When they arrive at his apartment, he discovers Fran passed out on his bed from an overdose of sleeping pills. He ditches the woman from the bar and enlists his neighbor Dr. Dreyfuss to revive Fran. Baxter implies that he was responsible for the incident; Dreyfuss scolds him for philandering and advises him to "be a mensch."

Fran spends two days recuperating in Baxter's apartment, during which a bond develops between them, especially after he confesses to an earlier suicide attempt over unrequited love. Fran says that she has always suffered bad luck in her love life.

As Baxter prepares a romantic dinner, one of the managers arrives for a tryst. Baxter persuades him and his companion to leave, but the manager recognizes Fran and later informs his colleagues. They are annoyed that they have not had the same ready access to the apartment since Baxter's promotion. When Fran's brother-in-law Karl shows up at the office building looking for her, the managers send him to the apartment. Baxter deflects Karl's anger over Fran's wayward behavior by once again assuming all responsibility. Karl punches him, and as she leaves, Fran kisses Baxter for protecting her.

When Sheldrake learns that Miss Olsen told Fran about his affairs, he fires her; she retaliates by spilling all to Sheldrake's wife, who promptly throws him out. Sheldrake welcomes this as an excuse to pursue Fran, although she hints that she is losing interest. Having promoted Baxter to an even higher position, Sheldrake expects Baxter to lend him the key to his apartment yet again so that he can take Fran there. Instead, Baxter gives him back the key to the building's "executive washroom", proclaiming that he has decided to become a mensch, and quits the firm. He decides to move out of the apartment and begins to pack his belongings.

That night at a New Year's Eve party, Sheldrake indignantly tells Fran about Baxter quitting, disclosing that Baxter refused to let him use his apartment, particularly with Fran. She abandons Sheldrake and runs to the apartment. At the door, she hears an apparent gunshot, but Baxter then opens the door holding a bottle of just-opened champagne. Baxter declares his love for her. “Shut up and deal,” she says, smiling, and they resume a game of gin rummy that they had left unfinished earlier.

Cast

[edit]

- Jack Lemmon as Calvin Clifford (CC) "Bud" Baxter

- Shirley MacLaine as Fran Kubelik

- Fred MacMurray as Jeff D Sheldrake, personnel manager, Baxter's boss and apartment user

- Ray Walston as Joe Dobisch, office manager and Baxter apartment user

- Jack Kruschen as Dr David Dreyfuss, Baxter's neighbor

- Frances Weintraub Lax as landlady Mrs Lieberman, always accompanied by her little dog Oscar

- David Lewis as Al Kirkeby, manager and Baxter apartment user

- Edie Adams as Miss Olsen

- Hope Holiday as Mrs Margie MacDougall

- Joan Shawlee as Sylvia

- Naomi Stevens as Mrs Mildred Dreyfuss

- Johnny Seven as Karl Matuschka (Fran's cab driving brother-in-law)

- Joyce Jameson as the blonde in the bar

- Hal Smith as Santa Claus in the bar

- Willard Waterman as Mr Vanderhoff, manager and Baxter apartment user

- David White as Mr Eichelberger, manager and Baxter apartment user

Production

[edit]

Immediately following the success of Some Like It Hot, Wilder and Diamond wished to make another film with Jack Lemmon. Wilder had originally planned to cast Paul Douglas as Sheldrake; however, after he died unexpectedly, Fred MacMurray was cast.

The initial concept was inspired by Brief Encounter by Noël Coward, in which Laura Jesson (Celia Johnson) meets Alec Harvey (Trevor Howard) for a thwarted tryst in his friend's apartment. However, Wilder was unable to make a film about adultery in the 1940s due to Hays Code restrictions. Wilder and Diamond also based the film partially on a Hollywood scandal in which agent Jennings Lang was shot by producer Walter Wanger for having an affair with Wanger's wife, actress Joan Bennett; during the affair, Lang had used a low-level employee's apartment for trysts.[5] Another element of the plot was based on the experience of one of Diamond's friends, who returned home after breaking up with his girlfriend to find that she had committed suicide in his bed.[citation needed]

Although Wilder generally required his actors to adhere exactly to the script, he allowed Lemmon to improvise in two scenes. In one scene, he squirts a bottle of nasal spray across the room, and in another, he sings while cooking spaghetti (which he strains through the grid of a tennis racket). In another scene, where Lemmon was supposed to mime being punched, he failed to move correctly, and was accidentally knocked down. Wilder chose to use the shot of the genuine punch in the film. Lemmon also caught a cold when one scene on a park bench was filmed in sub-zero weather.[citation needed]

Art director Alexandre Trauner used forced perspective to create the set of a large insurance company office. The set appeared to be a very long room full of desks and workers; however, successively smaller people and desks were placed to the back of the room, ending up with children. He designed the set of Baxter's apartment to appear smaller and shabbier than the spacious apartments that usually appeared in films of the day. He used items from thrift stores and even some of Wilder's own furniture for the set.[7]

Music

[edit]The film's title theme, written by Charles Williams and originally titled "Jealous Lover", was first heard in the 1949 film The Romantic Age.[8][9][10] A recording by Ferrante & Teicher, released as "Theme from The Apartment", reached #10 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart later in 1960.

Reception

[edit]

The film made double its $3 million budget at the US and Canadian box office in 1960.[11][12][13] Critics were split on The Apartment.[11][14] Time and Newsweek praised it,[12] as did The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther, who called the film "gleeful, tender, and even sentimental" and Wilder's direction "ingenious".[15] Esquire critic Dwight Macdonald gave the film a poor review,[14] calling it "a paradigm of corny avantgardism".[16] Others took issue with the film's controversial depictions of infidelity and adultery,[14] with critic Hollis Alpert of the Saturday Review dismissing it as "a dirty fairy tale".[11]

MacMurray, having generally played guileless characters, related that after the film's release he was accosted by women in the street who berated him for making a "dirty filthy movie", and one of them hit him with her purse.[7]

In 2001, Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert gave the film four stars out of four, and added it to his Great Movies list.[17] The film critic Clarisse Loughrey has identified it as one of her two favorite movies, along with the 2010 film Boy.[18] The film holds a 93% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 103 reviews with an average rating of 8.8/10; the site's consensus states that "Director Billy Wilder's customary cynicism is leavened here by tender humor, romance, and genuine pathos".[19] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 94 out of 100 based on 21 reviews, and was awarded the "Must-See" badge.[20]

Awards and nominations

[edit]Although Lemmon did not win the Oscar, Kevin Spacey dedicated his Oscar for American Beauty (1999) to Lemmon's performance. According to the behind-the-scenes feature on the American Beauty DVD, the film's director, Sam Mendes, had watched The Apartment (among other classic American films) as inspiration in preparation for shooting his film.

Within a few years after The Apartment's release, the routine use of black-and-white film in Hollywood ended. Since The Apartment only two black-and-white movies have won the Academy Award for Best Picture: Schindler's List (1993) and The Artist (2011) (Oppenheimer was in partial black and white).

In 1994, The Apartment was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. In 2002, a poll of film directors conducted by Sight and Sound magazine listed the film as the 14th greatest film of all time (tied with La Dolce Vita).[23] In the 2012 poll by the same magazine directors voted the film 44th greatest of all time.[24] The film was included in "The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made" in 2002.[25] In 2006, Premiere voted this film as one of "The 50 Greatest Comedies Of All Time". The Writers Guild of America ranked the film's screenplay (written by Billy Wilder & I.A.L. Diamond.) the 15th greatest ever.[26] In 2015, The Apartment ranked 24th on BBC's "100 Greatest American Films" list, voted on by film critics from around the world.[27] The film was selected as the 27th best comedy of all time in a poll of 253 film critics from 52 countries conducted by the BBC in 2017.[28]

American Film Institute lists:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (#93),[29]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs (#20),[30]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions (#62),[31]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) (#80).[32]

Stage adaptation

[edit]In 1968, Burt Bacharach, Hal David and Neil Simon created a musical adaptation titled Promises, Promises which opened on Broadway at the Shubert Theatre in New York City. Starring Jerry Orbach, Jill O'Hara and Edward Winter in the roles of Chuck, Fran and Sheldrake, the production closed in 1972. An all-star revival began in 2010 with Sean Hayes, Kristin Chenoweth and Tony Goldwyn as the three leads; this version added the Bacharach-David compositions "I Say a Little Prayer" and "A House Is Not a Home" to the roster.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tied with Sons and Lovers.

- ^ Tied with Jack Cardiff for Sons and Lovers.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c The Apartment at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ "The Apartment (1960)". The Numbers. Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ^ "25 Films Added to National Registry". The New York Times. November 15, 1994. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ Billy Wilder Interviews: Conversations with Filmmakers Series

- ^ Leek, Gideon (October 9, 2024). "The Man and The Crowd (1928): Photography, Film, and Fate". The Public Domain Review. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

in his 1960 film The Apartment, the Austrian filmmaker Billy Wilder cribbed the sequence to introduce Jack Lemon at his desk.

- ^ a b Chandler, Charlotte. Nobody's perfect: Billy Wilder : a personal biography.

- ^ 5107 Charles Williams & The Queen's Hall Light Orchestra at GuildMusic.com. Archived from Charles Williams at GuildMusic.com

- ^ Eldridge, Jeff. FSM: The Apartment FilmScoreMonthly.com

- ^ Adoph Deutsch's "The Apartment" w/ Andre Previn's "The Fortune Cookie" Kritzerland.com

- ^ a b c Fuller, Graham (June 18, 2000). "An Undervalued American Classic". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Apartment (1960)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 170

- ^ a b c Phillips, Gene D. (2010). Some Like It Wilder: The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder. Lexington, Kentucky, USA: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2570-1.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (June 16, 1960). "Busy 'Apartment':Jack Lemmon Scores in Billy Wilder Film". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Horrocks, Roger (2001). Len Lye: A Biography. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press. p. 257. ISBN 1-86940-247-2. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 22, 2001). "Great Movie: The Apartment".

- ^ "Kino Society". Archived from the original on November 18, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ "The Apartment (1960)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ "The Apartment Reviews - Metacritic". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "The 33rd Academy Awards (1961) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. October 5, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ^ "NY Times: The Apartment". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ "BFI | Sight & Sound | Top Ten Poll 2002 – The rest of the directors' list". Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ^ "Directors' Top 100". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 9, 2016.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. 2002. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ^ "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "100 Greatest American Films". BBC. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "The 100 greatest comedies of all time". BBC Culture. August 22, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

External links

[edit]- The Apartment essay by Kyle Westphal at National Film Registry

- The Apartment essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 566-558

Quotations related to The Apartment at Wikiquote

Quotations related to The Apartment at Wikiquote- The Apartment at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Apartment at IMDb

- The Apartment at AllMovie

- The Apartment at the TCM Movie Database

- The Apartment at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1960 films

- 1960s American films

- 1960 comedy-drama films

- 1960 romantic comedy films

- 1960s business films

- 1960s Christmas comedy-drama films

- 1960s romantic comedy-drama films

- 1960s sex comedy films

- Films about adultery in the United States

- American black-and-white films

- American business films

- American Christmas comedy-drama films

- American romantic comedy-drama films

- American satirical films

- American sex comedy-drama films

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Best Musical or Comedy Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- 1960s English-language films

- Films about businesspeople

- Films about depression

- Films directed by Billy Wilder

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actress Golden Globe winning performance

- Films scored by Adolph Deutsch

- Films set in apartment buildings

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in New York City

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Directing Academy Award

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Billy Wilder

- Films with screenplays by I. A. L. Diamond

- Films set in 1959

- Films set in offices

- Films set around New Year

- United Artists films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Workplace comedy films

- English-language romantic comedy-drama films

- English-language sex comedy-drama films

- English-language Christmas comedy-drama films

- Christmas romance films